Believe it or not, as long as the book was, there were still some Snow White-related topics that we just had to omit for lack of space. One of them was the extraordinary afterlife that Frank Churchill’s music enjoyed, long after the release of the film. The success of “Some Day My Prince Will Come” in the popular-music market of the late 1930s and early 1940s—the fact that a romantic ballad, written for an animated cartoon, had joined the ranks of enduring standards in American music—was remarkable enough, and helped to ensure once and for all Churchill’s place in music history.

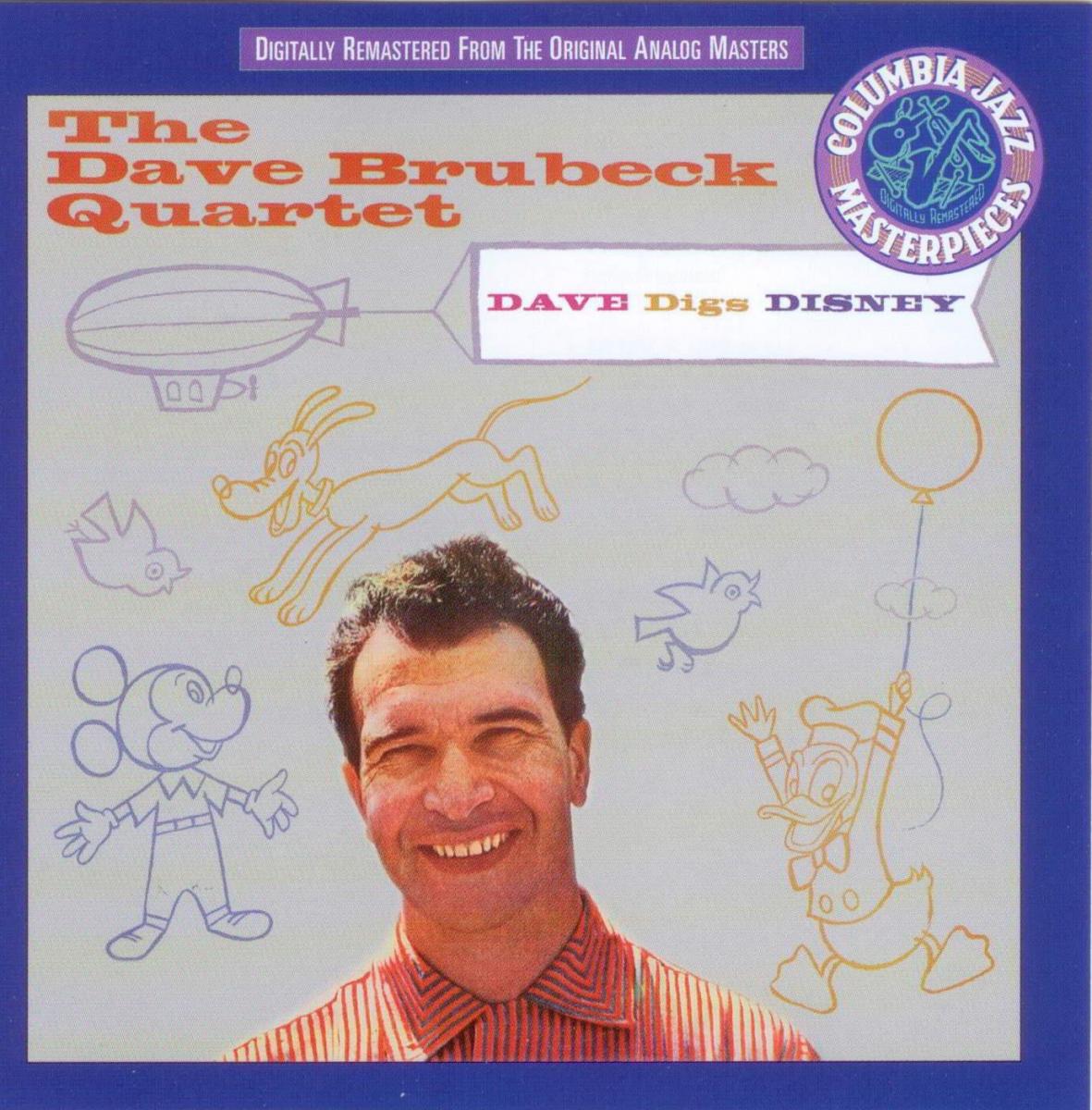

But then, a full twenty years after Snow White’s release, “Some Day” resurfaced in a new light, one that could hardly have been anticipated. In 1957, jazz giant Dave Brubeck spent a day with his family at then-new Disneyland, and was inspired to record a complete album of Disney tunes. It wasn’t an unusually challenging project, since the Brubeck Quartet already included quite a number of Disney songs in its standard repertoire. After a few days in the studio in late June 1957, the Quartet emerged with a new LP: Dave Digs Disney—a full program of songs from Disney features, reinterpreted by a top jazz stylist and his band.  The set included three songs from Snow White—(four, technically, since Brubeck’s arrangement of “Heigh Ho” began and ended with the interpolated strains of “Dig Dig Dig”)—but the standout selection, the one that made the jazz world sit up and take notice, was “Some Day My Prince Will Come.”

The set included three songs from Snow White—(four, technically, since Brubeck’s arrangement of “Heigh Ho” began and ended with the interpolated strains of “Dig Dig Dig”)—but the standout selection, the one that made the jazz world sit up and take notice, was “Some Day My Prince Will Come.”

This eight-minute cut, like the original song itself, still makes compelling listening today. Brubeck opens and closes the recording with a more or less straight reading of the chorus, tenderly preserving the subtleties of Churchill’s melody, while at the same time infusing it with what producer George Avakian, in the album’s liner notes, called “Brubeckian romanticism.” In between he trades improvisational solos with alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, and indulges his favored device of playing one time signature against another.

(Dave Digs Disney is still available today on CD, and includes, as a bonus, two cuts that were not available on the LP: Hilliard and Fain’s “Very Good Advice” from Alice in Wonderland, and David/Hoffman/Livingston’s “So This is Love” from Cinderella.)

Brubeck’s breakthrough recording made an impact on the music world, and soon “Some Day” was widely recorded by other performers, its existing status as a pop-music standard supplemented by new recognition in the jazz world. Something about Churchill’s fragile chord structure, composed with such apparent ease and spontaneity in the fall of 1934, captured an ineffable wistfulness that inspired these performers of a later day.

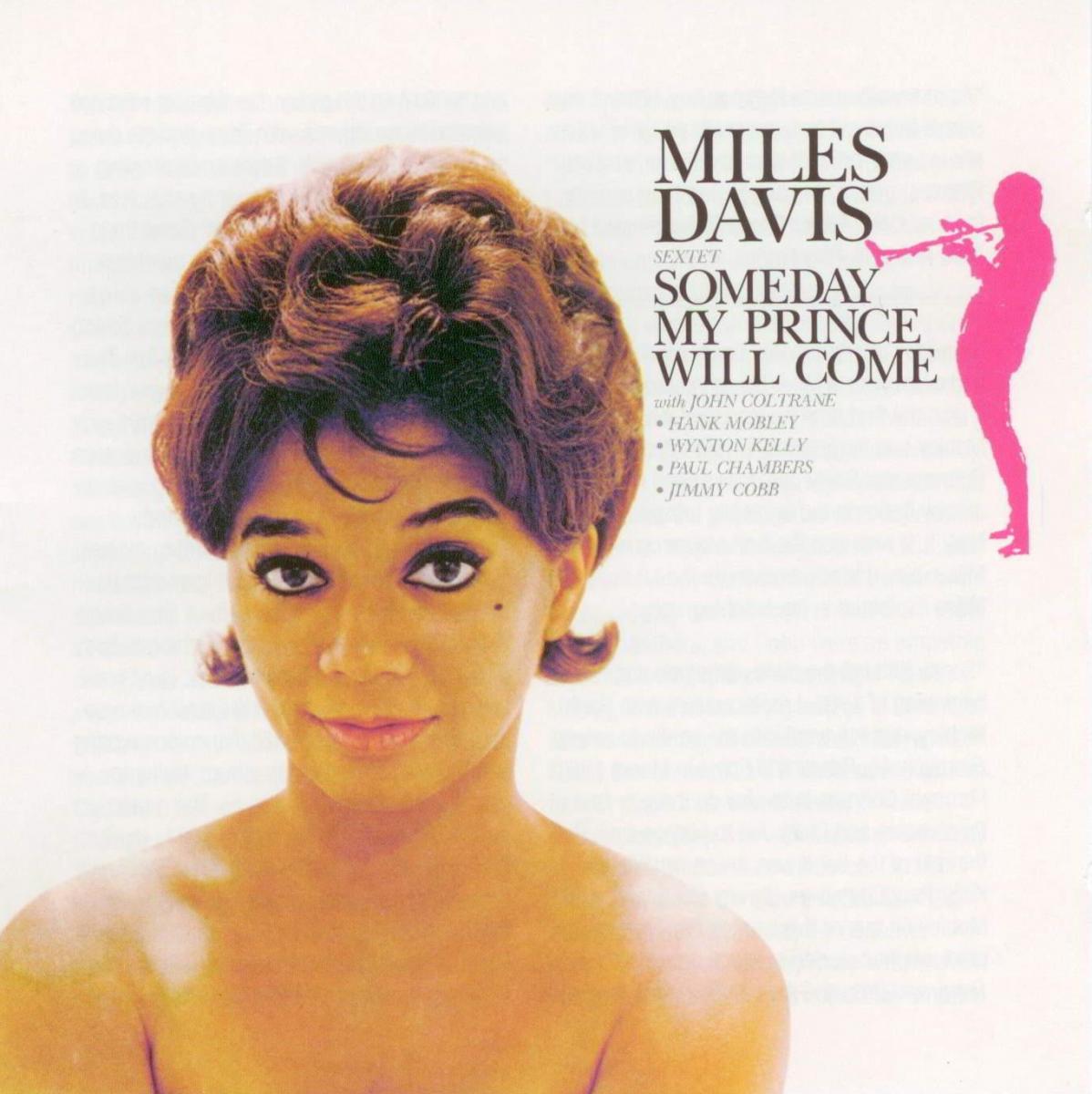

One of the more notable followup recordings was that by the Miles Davis Sextet in 1961. The album Someday My Prince Will Come is still regarded as a milestone by Davis enthusiasts today, partly because it marked the final chapter in his association with another jazz legend, John Coltrane. The album opens with another extended recording (just over nine minutes) of “Some Day,” and if anything, Davis’s version is even more laid-back than Brubeck’s. His muted trumpet warmly caresses the melody, and when he, Coltrane, and others essay their solos, no one wanders very far from Churchill’s original territory. The album closes with a second, shorter alternate take of the song, perhaps a trifle more up-tempo than the first, but still muted and restrained.

The album Someday My Prince Will Come is still regarded as a milestone by Davis enthusiasts today, partly because it marked the final chapter in his association with another jazz legend, John Coltrane. The album opens with another extended recording (just over nine minutes) of “Some Day,” and if anything, Davis’s version is even more laid-back than Brubeck’s. His muted trumpet warmly caresses the melody, and when he, Coltrane, and others essay their solos, no one wanders very far from Churchill’s original territory. The album closes with a second, shorter alternate take of the song, perhaps a trifle more up-tempo than the first, but still muted and restrained.

(Someday My Prince Will Come is also still available on CD, and again, in some versions, includes bonus material—including yet a third performance of “Some Day,” recorded live in April 1961, before the album had been released.)

These and other recordings add an unexpected but potent dimension to the legacy of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. They represent tributes by distinguished musicians to a colleague of an earlier generation—treating Churchill’s melodic invention with respect, and at the same time opening up facets of it to new appreciation.

Special thanks to Ben Urish and Margaret Kaufman.

Some Day My Prince Will Come: The Jazz Years

Book Reference: