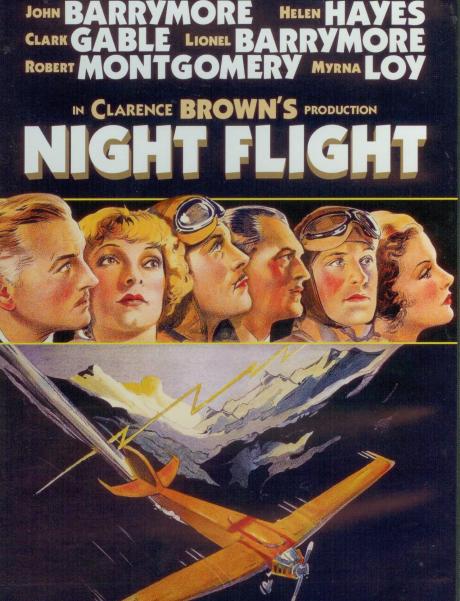

MGM, 1933. Director: Clarence Brown. Screenplay: Oliver H.P. Garrett and [uncredited] John Monk Saunders, based on the novel by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Camera: Oliver T. Marsh and [aerial photography] Elmer Dyer and Charles Marshall. Film editor: Hal C. Kern. Cast: John Barrymore, Helen Hayes, Clark Gable, Lionel Barrymore, Robert Montgomery, Myrna Loy, William Gargan.

April is the month of the TCM Classic Film Festival, one of the most eagerly anticipated events of the year for the film enthusiast. Speaking for myself, this year’s approaching event brings to mind thoughts of previous year’s festivals, and the happy cinematic discoveries they’ve produced. One of the most notable was Night Flight, an MGM feature unveiled at the 2011 festival. Originally released in 1933 to a disappointing reception at the box office, Night Flight had been quickly forgotten and, in subsequent years, had unaccountably fallen through the cracks of film history. By 2011 it had been out of general circulation for nearly 70 years, and virtually none of the festival attendees had ever seen it. Taking advantage of a newly restored print, TCM presented it with some hesitation. Viewers, including this one, attended the showing for the pleasure of witnessing an unearthed rarity, but with low expectations for the film itself.

What a pleasant surprise! Night Flight turned out to be a thoroughly engaging film, intelligently written and directed, glistening with MGM production values, and lingering in the memory long after the screening ended—so much so that one had to wonder why it had fared so poorly at the box office, even in a year as rich with competing classic films as 1933. One reason may be the darkness of its plot; the narrative ventures into grim subject matter and faces it unflinchingly. But this is a quality that has aged well in the intervening decades, and Night Flight is quite possibly more appealing to today’s film enthusiast than to its original audiences.

As its title suggests, the film portrays the pioneers of aviation who first ventured to fly mail and other cargo at night, before the development of advanced instrument flying and other safety measures. It’s built around a cunning plot device: a child in Rio de Janeiro is desperately ill and needs a serum that can only be found in Santiago, Chile—the far side of the continent, separated from Rio by forbidding terrain and wild, unpredictable weather. The task of rushing the serum to the patient falls to an assorted series of characters, played in linked vignettes by a generous selection of MGM contract stars. A glance at the (partial) cast list above will reveal the abundance of talent on display here: this is Grand Hotel with wings.

That, indeed, was evidently one of the main factors that motivated David O. Selznick to produce the film. Selznick had recently arrived at MGM and, inspired by the success of the studio’s Grand Hotel, had made his mark with an all-star prestige picture of his own: Dinner at Eight, which of course became a classic in its own right. Night Flight was his followup. It’s a worthy successor, fully as elegant and literate as its predecessors. In addition, it’s far more cinematic in some ways: the story is not stagebound but skips around the South American continent, its disparate locations linked by smooth and imaginative opticals. The interiors are beautifully photographed, some of them marked by moody, atmospheric lighting that enhances the drama without distracting from it.

And the film becomes doubly cinematic by dint of Selznick’s other major motivation: to produce an aerial epic film. The 1927 release of Paramount’s ambitious World War film, Wings, had proven a landmark in more ways than one, spawning a host of imitations from other studios. Howard Hughes had been inspired to produce his own war-aviation picture, Hell’s Angels, hiring some of the same cameramen who had filmed the brilliant aerial scenes in Wings. Now, in 1933, Selznick in his turn determined to produce a Hell’s Angels of his own. The flying scenes in Night Flight haven’t the epic sweep of the earlier classics, but Selznick did engage a crew of aerial cameramen, at least one of whom, Elmer Dyer, had worked on Hell’s Angels. The flying shots, with the rugged Rocky Mountains substituting for the Andes, are nothing short of spectacular, with towering cloud formations dwarfing the tiny, vulnerable planes. MGM publicity proudly announced that some of the “night flight” scenes had been filmed with an innovative use of infrared photography.

With so many different qualities going for it, Night Flight is a difficult film to categorize—perhaps another reason for its tepid box-office reaction in 1933. But it’s a memorable film under any label, and we can be grateful to TCM for resurrecting it to view. And we can only wonder what new and unexpected treasures may be unveiled at this year’s festival!