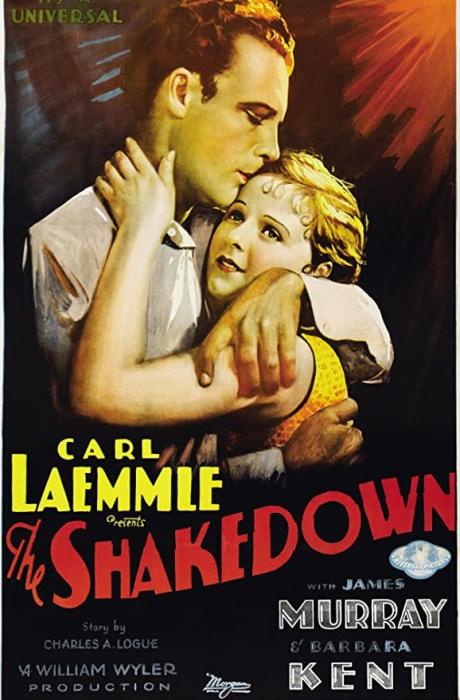

Universal, 1929. Director: William Wyler. Scenario: Charles A. Logue and Clarence J. Marks. Camera: Charles Stumar and Jerome Ash. Film editors: Lloyd Nosler and Richard Cahoon. Cast: James Murray, Barbara Kent, George Kotsonaros, Wheeler Oakman, Jack Hanlon, Harry Gribbon.

No other film festival in the world is quite like Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. For nearly four decades it has been the world’s leading silent-film festival, setting the gold standard for all the others. Located in the lovely Italian town of Pordenone, it draws the top silent-film scholars from around the world and presents a tremendously varied program—new restorations, fragments and rediscoveries, occasional refresher screenings of the established classics—pulled from the leading international archives. With a thoughtful, professional, resourceful staff and an endless fund of inventive programming ideas, the Pordenone festival has done incalculable good in nurturing a worldwide appreciation of silent cinema. The directors’ resourcefulness has been put to the test in 2020 by the global pandemic which has similarly impacted everything else in our lives—and, once again, they have responded to the problem with an ingenious solution. More about that presently.

The international influence of the Giornate has been felt in countless ways, not least in its screenings of long-lost or long-forgotten films, reintroducing them to the silent-film community at large and reshaping our established perceptions of the silent era. One striking example is William Wyler’s The Shakedown, shown at the festival in 1998. Wyler is, of course, remembered today primarily for his sound films. But the Giornate had mounted a silent Wyler retrospective in 1994 that revealed his silent output—like that of Alfred Hitchcock, who has likewise been accorded a sensational Pordenone retrospective—as already the work of a gifted filmmaker. Then, in 1998, the festival followed up with the newly rediscovered The Shakedown. This was an extremely obscure title, and many of us who attended the screening had never heard of it before.

Then the movie started—and what a movie! The screening was an electrifying experience, one that left many in the audience open-mouthed with astonishment. This unassuming picture, so long forgotten, unexpectedly proved to be a sparkling little gem of filmmaking. By the end of the week it had become the surprise hit of the 1998 festival. Attendees returned to their homes with that memory fresh in their minds, and soon The Shakedown began to appear on the programs of other festivals, and to reclaim its place in silent-screen history. In 2020, I’m happy to say, Kino Lorber has issued it on Blu-Ray so that all can experience it for themselves.

For the benefit of those who have not yet seen the film, I will not dwell on details. Briefly, it’s the story of a small-time grifter (James Murray) who arrives in a new town, intending to fleece the locals, but whose life is unexpectedly changed by his encounters with a lunch-counter waitress (Barbara Kent) and a scrappy, street-smart orphan boy (Jack Hanlon). It’s a story with familiar themes, but it’s quite engaging here, pictured with warmth and restraint. The cast is excellent. James Murray is remembered today, if at all, only for his appearance in King Vidor’s The Crowd, but here gives a nicely nuanced performance that proves that his work in the Vidor classic was no fluke—and makes the tragic contours of his later life still more poignant.  Barbara Kent, so oddly overlooked today and yet familiar from such major films as Flesh and the Devil and Paul Fejos’ Lonesome, gives a quietly moving performance and adds much to the charm of this film.

Barbara Kent, so oddly overlooked today and yet familiar from such major films as Flesh and the Devil and Paul Fejos’ Lonesome, gives a quietly moving performance and adds much to the charm of this film.

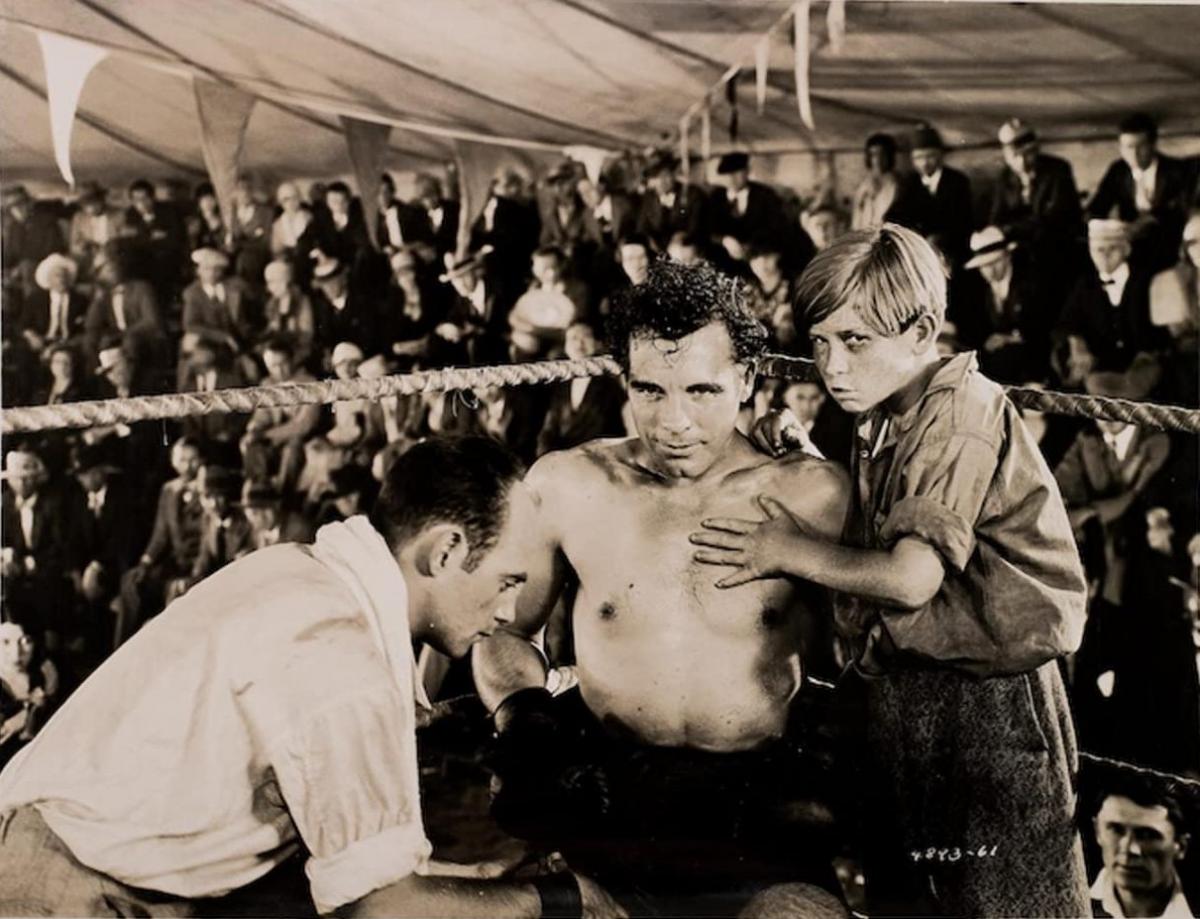

But in a sense, the real star of the film is William Wyler himself. The Shakedown is one of that wave of late-1920s silents, produced on the cusp of the talking-picture revolution, that blossomed in a dazzling display of cinematic technique, as if to remind audiences just how much they were about to lose. (It’s also one of the many films of the period that were released in separate, part-talkie editions. Happily, the only version that seems to have survived is the all-silent version.) Beyond the story, beyond the cast, this is a movie that moves. If we needed any further proof that Wyler was a born filmmaker, The Shakedown provides it. Camera technique here is exemplary, conveying much of the plot through elegantly composed deep-focus shots. And the moving camera, that hallmark of the late silent period, is especially prominent here. The camera is rarely still in this film: tracking with characters as they walk along a sidewalk, riding swiftly up and down with Murray on an oil-derrick elevator, soaring into the air with characters on a Ferris wheel. In the climactic boxing match the camera is everywhere, circling and dodging around the pugilists, picturing them from high-angle shots, low-angle shots, bracing sudden point-of-view shots. In one scene Wyler cements his mastery of technique by tossing off an unexpected visual flourish that I will not attempt to describe here—but it brought an audible gasp from the Pordenone audience in 1998, and retains its punch on repeated viewings.

Again, The Shakedown is not an isolated case; many long-forgotten films have been reintroduced to the canon thanks to a Pordenone screening, extending and deepening our knowledge of the silent era. We can be grateful for the blessings provided by this essential festival, and can hope for many more as Le Giornate del Cinema Muto continues its good works indefinitely.

In 2020, of course, those blessings have come to us in a different form. For this edition, the Giornate went online—and the organizers found a characteristically creative way to do it. They prepared a special program for each day of the festival, each one streamed for 24 hours so that viewers in any time zone could enjoy it. Of course these innovative presentations lack the delightful experience of actually being in Pordenone—but, on the other hand, they make a taste of the festival available to many who could not otherwise attend. They may even point the way to future festival supplements. Ultimately they may succeed, not only in overcoming adversity, but in bringing the magic of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto to an exponentially larger worldwide audience.