Biograph, 1909. Director: D.W. Griffith. Camera: Billy Bitzer. Cast: Florence Lawrence, Adele De Garde, Marion Leonard, Linda Arvidson, Anita Hendrie.

February is the month of the Kansas Silent Film Festival, and the festival organizers never fail to deliver a program filled with highlights for the film enthusiast. This year is no exception. Adopting a centennial theme, their program features a generous banquet of 1923 silents, including many of the established classics but also some intriguing lesser-known treasures. As if all that were not enough, the program is topped off with a gem from our good friends at the Film Preservation Society. The Society is no stranger to this column; in the past I’ve highlighted a number of the long-missing silent features that they’ve preserved for posterity and made available to the home viewer on beautifully produced Blu-Ray discs. And, in fact, I’m taking this opportunity to call attention to those invaluable releases again.

Those rescued and restored features are exciting—but in the meantime, working quietly behind the scenes, FPS has been carrying on a parallel mission that may be even more exciting in the long run. They’ve taken on nothing less than the full restoration of all the films directed by D.W. Griffith at the Biograph company during his seminal five years there, 1908–1913. No regular reader of this column will need to be told what an historic endeavor that is. The Biograph years were, in a real sense, the birth of the movies: the years when Griffith took the existing technical properties of the motion picture and molded them into a language for telling a story on the screen. He did so by means of a staggering output of short films, numbering nearly 500 titles in the space of five years. By a miracle, nearly all of those short films have survived, but the majority have survived in inferior viewing copies that fall far short of the pictorial quality of the originals. In recent decades the technology of film preservation has improved to the point where the Griffith Biographs could be restored to their full visual excellence—but because of the colossal effort and prohibitive expense involved in restoring those hundreds of films, no one has been willing to tackle the job.

Until now. The FPS, a small independent organization, has addressed this monumental task in the only way that makes sense: carefully, methodically, one film at a time. At this writing they have progressed as far as the films produced in the spring of 1909, turning out clean, sharp, crisply mounted versions that display Griffith’s artistry in the best possible light—some of them for the first time in more than a century. One of those rescued gems, the 1909 split-reel drama The Medicine Bottle, will be shown this month in a featured spot at the Kansas festival.

As with so many of the Biographs, the plot of The Medicine Bottle is basically a simple setup for an experiment in film craft. Here, specifically, it’s an exercise in building suspense. Griffith had made suspenseful films before, and would go on to produce increasingly spectacular efforts with exciting “races to the rescue” (not all of which succeeded in rescuing the endangered party). The Medicine Bottle is notable in that there is no fast physical action; the suspense is generated entirely through editing, and demonstrates Griffith’s sure mastery of cinematic technique, even this early in his career.

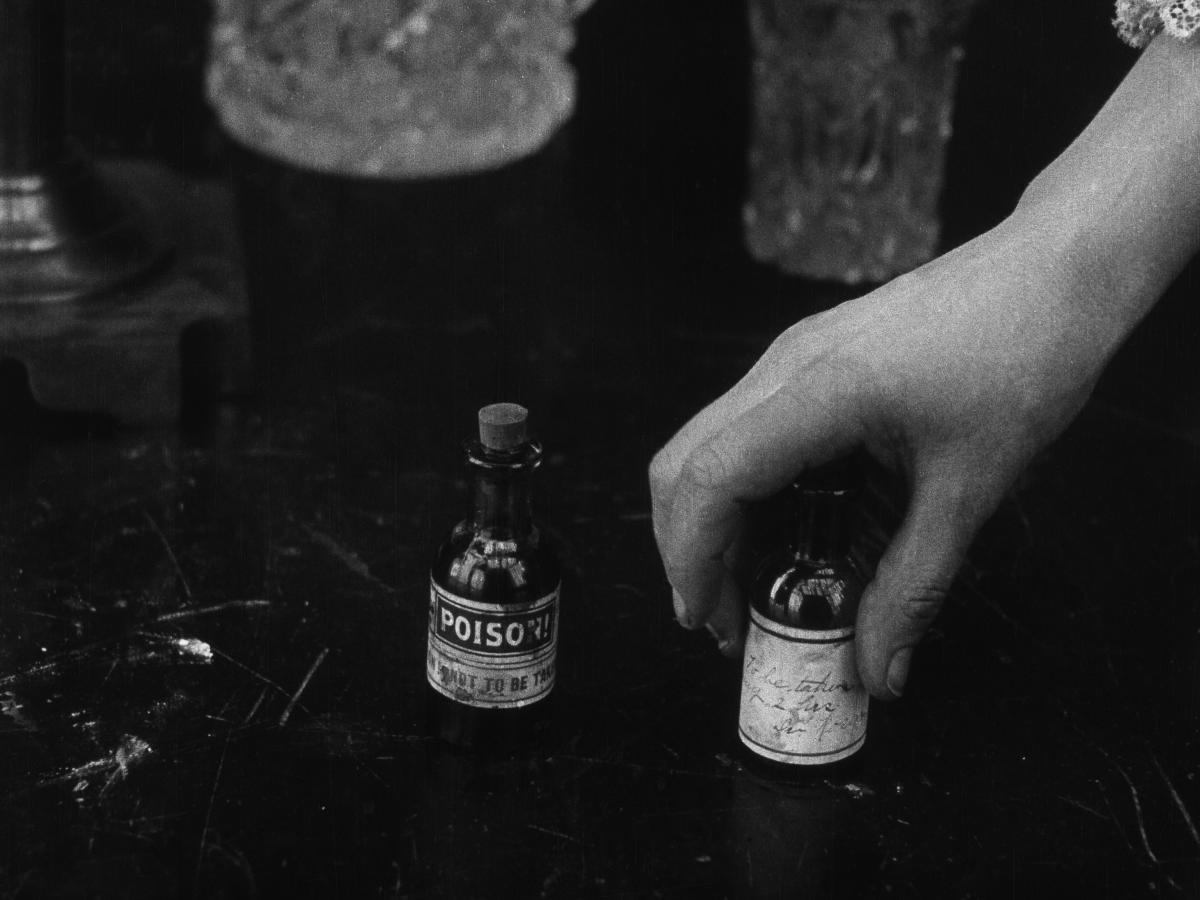

The story concerns Florence Lawrence, Griffith’s first featured leading lady, whose plan to attend a tea party (hosted by Marion Leonard, another busy Biograph regular) is complicated by the need to care for her invalid mother, who must be given medicine at a prescribed time. Florence leaves the patient in the care of her young daughter (Adele De Garde), with specific instructions to give Grandmother a dose of medicine at the predetermined hour.  But Florence cuts her hand just before leaving, and applies antiseptic to the cut. At the party, as the appointed hour approaches, she is horrified to realize that she has carelessly brought the medicine bottle with her, and it’s the antiseptic bottle that her daughter—who is too young to read the “Poison” label—is charged with administering to the old lady. Now everything depends on reaching the girl by telephone before she unknowingly poisons her grandmother. Griffith heightens the tension by crosscutting between Florence at the party, dutiful Adele at home, and the telephone-company switchboard, where several operators (one played by Linda Arvidson, then Griffith’s wife) are too busy chatting to bother with connecting calls.

But Florence cuts her hand just before leaving, and applies antiseptic to the cut. At the party, as the appointed hour approaches, she is horrified to realize that she has carelessly brought the medicine bottle with her, and it’s the antiseptic bottle that her daughter—who is too young to read the “Poison” label—is charged with administering to the old lady. Now everything depends on reaching the girl by telephone before she unknowingly poisons her grandmother. Griffith heightens the tension by crosscutting between Florence at the party, dutiful Adele at home, and the telephone-company switchboard, where several operators (one played by Linda Arvidson, then Griffith’s wife) are too busy chatting to bother with connecting calls.

Along with this display of editing skill, Griffith adds his usual quota of supplemental touches. Florence Lawrence’s performance in the leading role is notably nuanced. She’s essentially sympathetic, but just a bit selfish; before leaving for the party she has a stage “aside,” registering her petulant irritation at family health concerns that have infringed on her social plans. At the tea party there’s an intimate moment of comedy, probably improvised on the set, involving an annoying party guest. Historian Tracey Goessel, one of the principals behind FPS, has commented on this vignette: “It is over in a moment, the sort of sudden delight that casual viewers of silent films are likely to miss … The little comic moment bears no real relation to the narrative; has no true necessity. It simply is.” It’s also the kind of subtle visual detail that was totally lost in the soft, blurry viewing copies of the Biographs that have predominated for decades. Now, thanks to the efforts of a dedicated band of professionals, the full range of those cinematic embellishments is being restored for posterity. And attendees of this year’s Kansas festival will have the opportunity to see a sample for themselves.