Realart/Paramount, 1920. Director: William Desmond Taylor. Scenario: Julia Crawford Ivers. Camera: James C. Van Trees. Cast: Lewis Sargent, Ernest Butterworth, Clyde Fillmore, Grace Morse, Lila Lee, Elizabeth Janes, William Collier Jr.

For anyone who loves silent films, the month of October has a special place in the calendar. October is the month of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, the beloved international silent-film festival, held annually in Italy. For eight days, historians, archivists, and preservationists from around the world come together in the beautiful Italian town of Pordenone to share rarities, new discoveries, new restorations, and films that simply have been overlooked for generations. Silent-film history has been rewritten more than once based on the discoveries made at this festival, and not a few productive international collaborations have been forged between screenings in Pordenone.

I’m not attending this year, so as my tribute to the Giornate, I’m featuring a film that I saw for the first time in Pordenone. The Soul of Youth was shown there in 2007, presented in collaboration with the National Film Preservation Foundation, who were featured in this department last month in connection with their new DVD, Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive. In 2007 they were launching an earlier DVD set, Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film, 1900-1934, at the Giornate. Happily, the set is still available, and The Soul of Youth can still be seen there.

It’s worth seeking out, for several reasons. One is its director, William Desmond Taylor, whose life and career would be cut short so soon after making this film. I feel strongly that great filmmakers should be remembered for their talent, rather than the scandals sometimes associated with them, and Taylor gives a strong account of his talent in this picture. From the strikingly atmospheric opening scenes, photographed in low-key lighting, to the end, Taylor demonstrates a confident mastery of the filmmaker’s craft. The Soul of Youth is one of those films that combined an absorbing story with Progressive-era editorializing about social causes—one of the subgenres that silent films handled so much more effectively than talkies. This film takes on the trafficking of unwanted babies and the pitifully inadequate conditions of orphanages, but concentrates most of its social focus on the importance of the juvenile court system, in 1920 still a relatively new idea.

The Soul of Youth was produced by Realart Pictures, a subsidiary of Paramount, formed in 1919 to produce a specialized product line: quality films on a budget. Realart effected its cost savings largely through casting, featuring lesser-known or unknown players in its pictures. Easily the best-known player in The Soul of Youth is Lila Lee—who was, after all, a top-billed Paramount star and had already worked with both Cecil and William deMille—but her fleeting appearance here, in a minor role, seems inserted gratuitously to shore up the film’s box-office appeal. (Indeed, the film’s title, The Soul of Youth, seems calculated to suggest a connection with Lila’s 1919 starring vehicle The Heart of Youth!) In any case, two other players are of far more interest in this film. The young protagonist of the story is played by Lewis Sargent, a boy who had just starred in Taylor’s production of Huckleberry Finn. No child-star grooming or phony sentimentality in this portrayal; young Sargent comes across as an authentic, homely, natural, and thoroughly likeable kid. His performance alone is worth the price of admission.

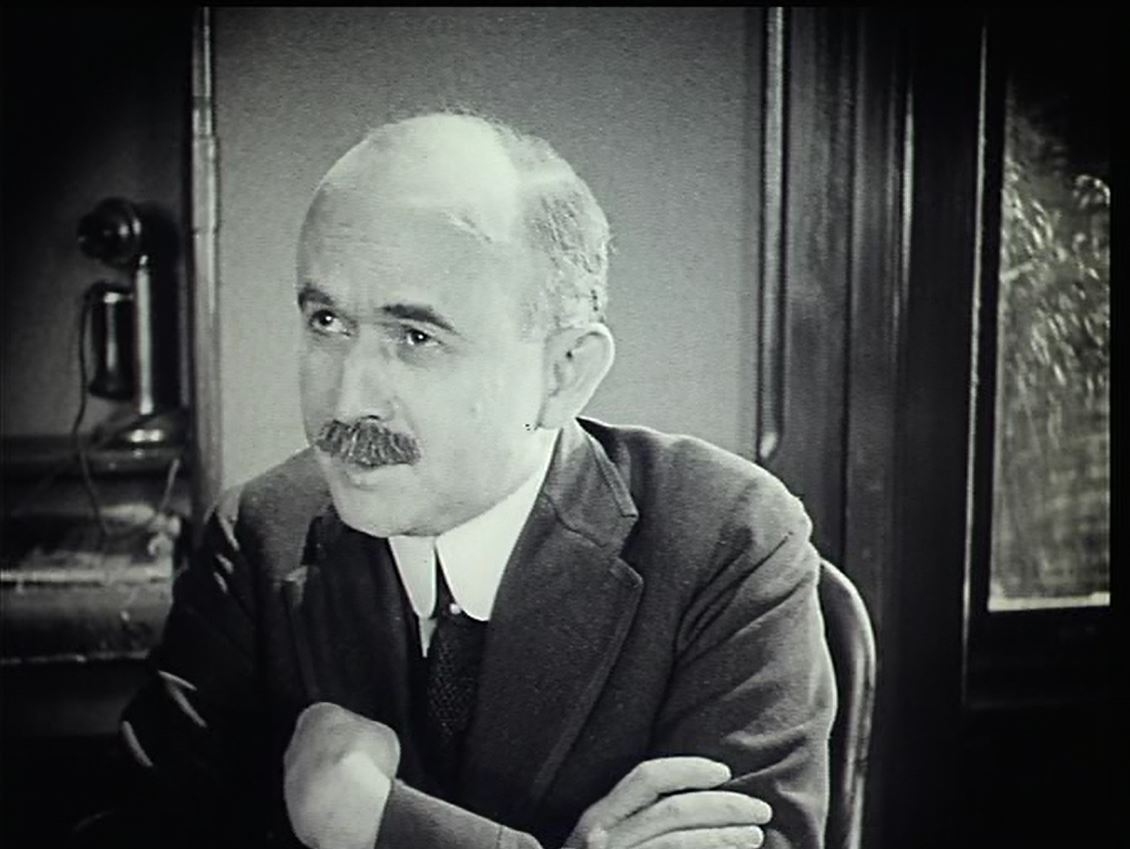

The other “player” of special note in The Soul of Youth is a nonprofessional: Judge Ben B. Lindsey, one of the founders of the juvenile court system, playing himself.

The Soul of Youth does open with a series of moralizing intertitles, more or less in the manner of Lois Weber, and it paints a less than subtle distinction between its good and evil characters. Viewers who object to these things—as I do not—should be advised that the film also offers a hard, unsentimental look at the wrongs of society, that it packs a surprising amount of sheer entertainment value along with its “message” content, and that Kevin Brownlow himself has described it as “exceptional,” praising its photography and art direction. The DVD transfer is made from a beautiful print in the Library of Congress, and replicates the original tinting. All in all it’s a thoroughly satisfying film, and I’m grateful to the Giornate, and the NFPF, for bringing this overlooked gem to my attention.