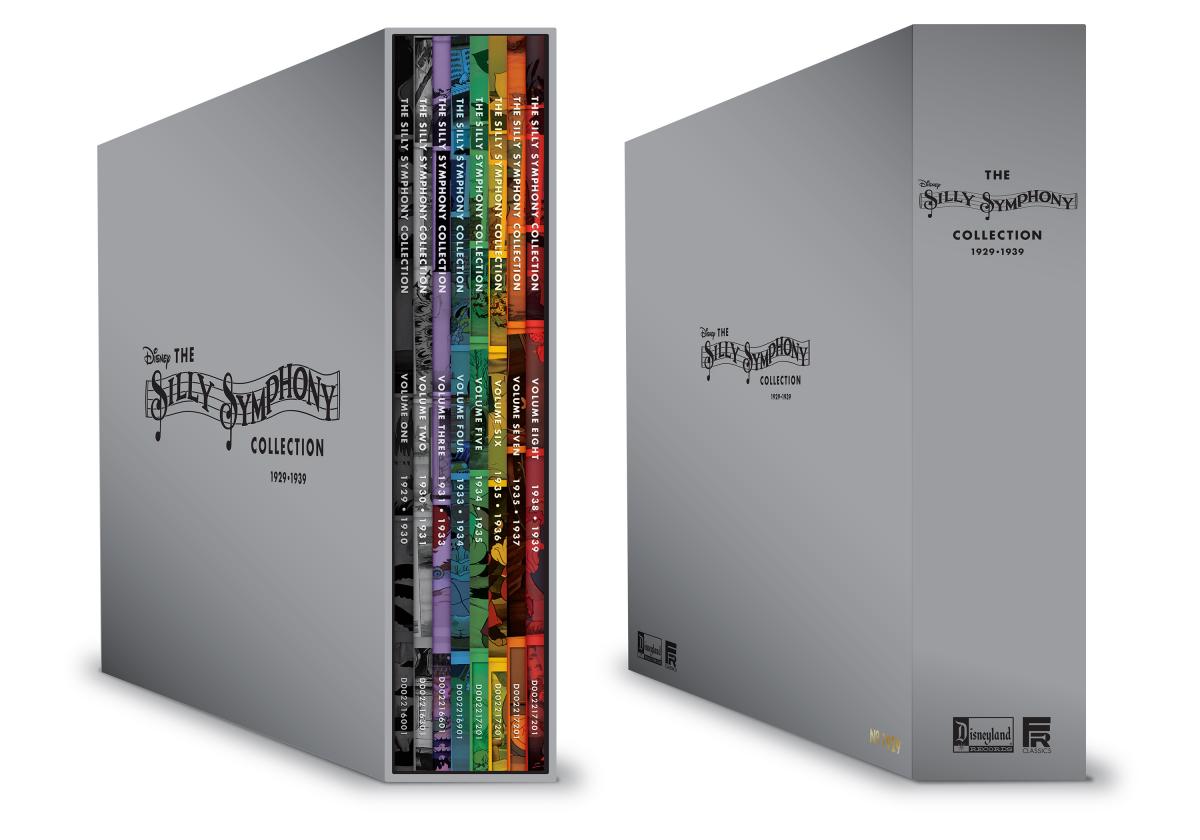

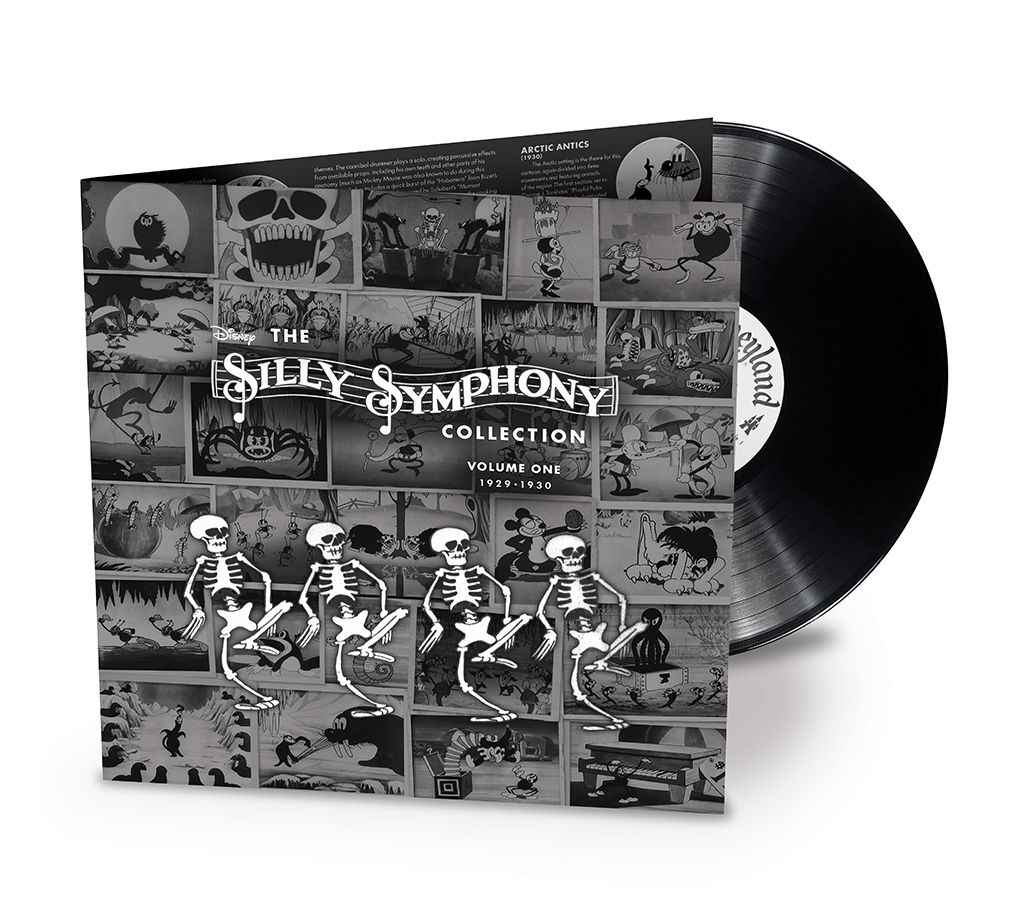

This isn’t a book, so it wouldn’t make sense to include it in the book section … but I was, and still am, really proud to be associated with this project! Eight double LPs, packaged together in a box, containing the complete soundtracks of all 75 Silly Symphonies! This massive effort was put together as a collaboration between Walt Disney Records and Fairfax Classics, and the sound was restored by Disney’s resident audio wizard, Randy Thornton. Russell Merritt and I were privileged to write the liner notes. Here’s a sampling of our notes from two of the volumes:

This isn’t a book, so it wouldn’t make sense to include it in the book section … but I was, and still am, really proud to be associated with this project! Eight double LPs, packaged together in a box, containing the complete soundtracks of all 75 Silly Symphonies! This massive effort was put together as a collaboration between Walt Disney Records and Fairfax Classics, and the sound was restored by Disney’s resident audio wizard, Randy Thornton. Russell Merritt and I were privileged to write the liner notes. Here’s a sampling of our notes from two of the volumes:

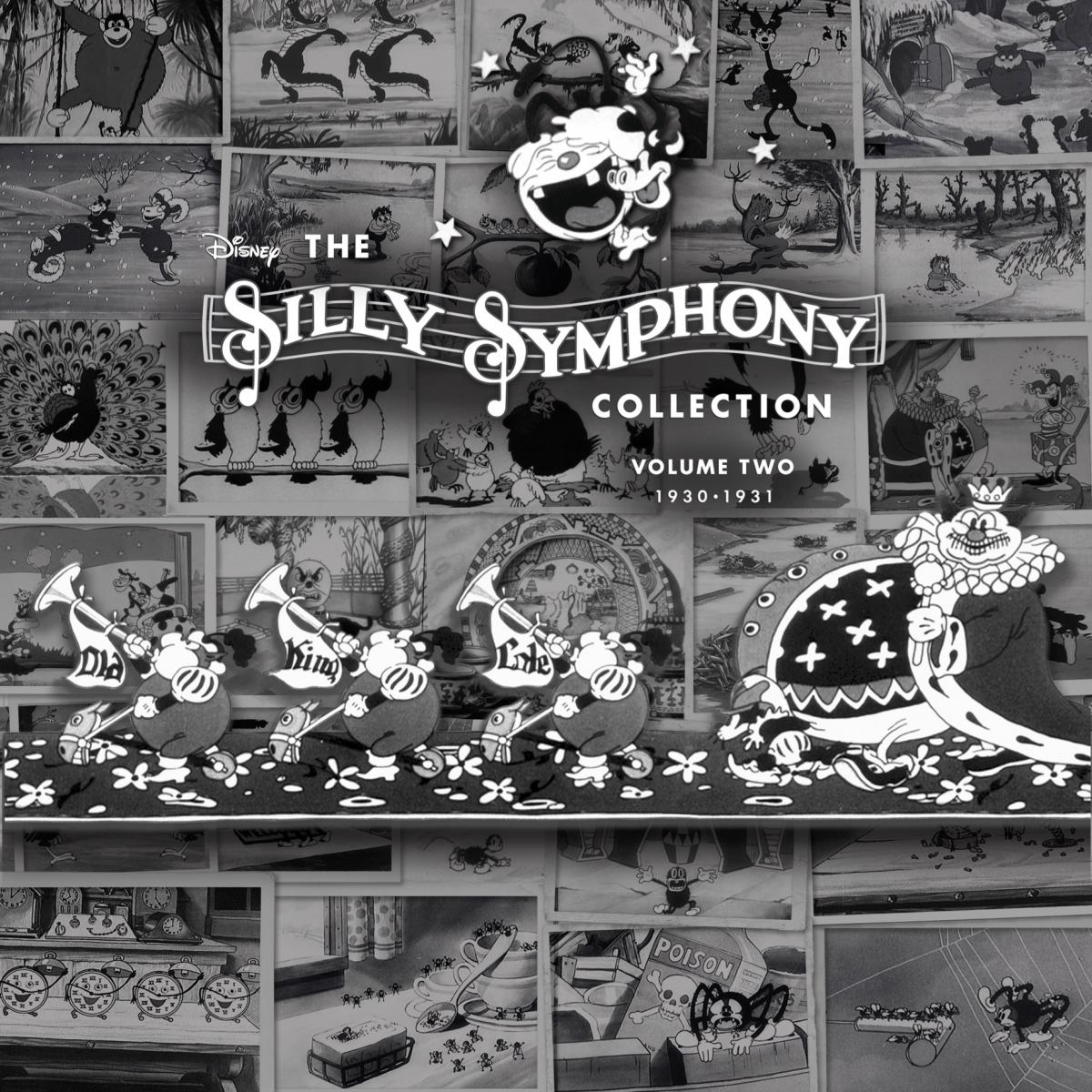

Vol. 2

BIRDS OF A FEATHER

Birds of a Feather—the title taken from a Mother Goose Wise Saying, “Birds of a feather flock together”—became the early prototype for a formula Disney would elaborate throughout the early ’30s, a comic counterpart to the collective ideology of the New Deal. The formula calls for a folk army to band together to defeat a lone dangerous bully who menaces the community. In this case, the predator is a soaring chicken hawk who swoops down to steal a mother hen’s black chick. In response, a blackbird sounds an alarm through a funnel, and a fighter squadron of small birds forms to the theme of Zamecnik’s “Allegro Furioso,” made famous several years earlier as the music for the air battles in Paramount’s Wings. With power dives, the squadron de-feathers and repels the chicken hawk, and the toddler returns unharmed to its mother.

The film was a hit from the get-go. Chaplin chose it to accompany City Lights for its London first run, where it is likely that Eisenstein saw it and noted the inventiveness of an early sequence where a preening peacock struts to the tune of “The Barcarolle.” Disney himself would re-form his folk army in ever more elaborate guises—sending bees, flies, dwarves, moths, and more birds into action to fight witches, wolves, and oversized thugs with ever more Surreal weaponry. But, though the army in this film never gets to fight with anything more elaborate than its beaks, the animation itself—especially the graceful flow of the chicken hawk’s wings and the dynamic staging of the mother hen’s dance—are among the film’s highlights.

The film was a hit from the get-go. Chaplin chose it to accompany City Lights for its London first run, where it is likely that Eisenstein saw it and noted the inventiveness of an early sequence where a preening peacock struts to the tune of “The Barcarolle.” Disney himself would re-form his folk army in ever more elaborate guises—sending bees, flies, dwarves, moths, and more birds into action to fight witches, wolves, and oversized thugs with ever more Surreal weaponry. But, though the army in this film never gets to fight with anything more elaborate than its beaks, the animation itself—especially the graceful flow of the chicken hawk’s wings and the dynamic staging of the mother hen’s dance—are among the film’s highlights.

The camerawork too showed notable refinement. By now the studio had replaced its Pathé camera with a Universal, which was mounted so that it could be raised, lowered, and rotated a full 360 degrees; Birds of a Feather takes advantage of the new flexibility with a bravura aerial scene in which the camera, swooping down on the hawk, takes the point of view of a charging bird.

MOTHER GOOSE MELODIES

This ambitious short announced a new direction for the Silly Symphonies, breaking new ground for the series both visually and musically. Mother Goose Melodies is essentially a revue, built around the theme of nursery rhymes and other childhood fantasies, and presided over by Old King Cole. Listeners, exploring the Symphonies by way of their music, will notice a dramatic departure from the earlier entries, which had leaned heavily on a repertoire of light classics and vintage popular songs, mostly instrumental. This short, instead, features a largely original score—albeit one that incorporates snatches of “Three Blind Mice,” “Jack and Jill,” and other traditional children’s songs—and lots of singing. The voice of King Cole is supplied by Allan Watson, who would voice similar characters in the Symphonies over the next few years. Little Jack Horner’s voice is none other than Walt Disney, singing in a falsetto not unlike the one he was concurrently providing for Mickey Mouse.

There’s some question about authorship of the music for this short. Bert Lewis was still at the studio and would continue to contribute scores to Disney cartoons for several more years, but a major new talent, Frank Churchill, had recently joined the staff. It’s possible that both composers contributed to the score of Mother Goose Melodies.

One concession to the traditional Silly Symphony musical diet is Josef Franz Wagner’s “Under the Double Eagle” (1893). This piece underscores the opening scene, a long pan in which a procession of trumpeters, drummers, and pages prepare the way for King Cole’s entrance. Both the music and the animation would be repurposed in 1932 for a special Academy Awards short—and again in 1939 for an advertising film for Standard Oil!

Vol. 6

Vol. 6

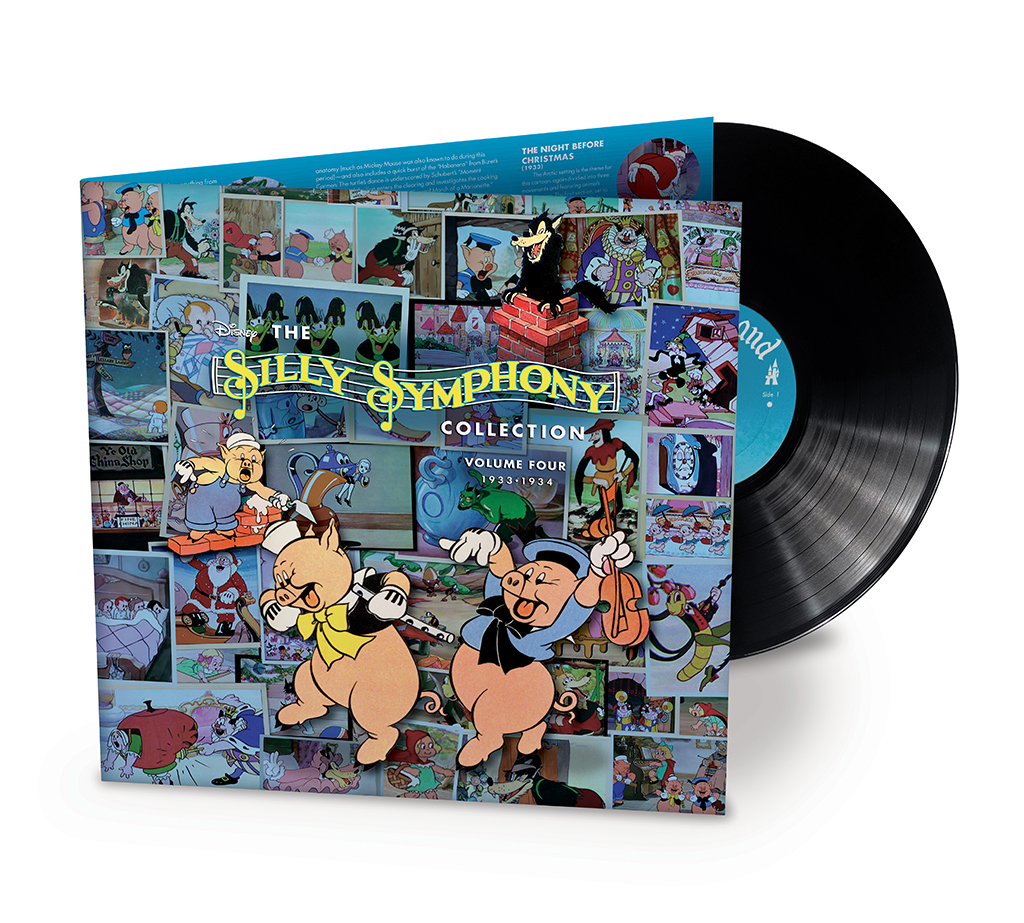

MUSIC LAND

Amazingly enough, Disney didn’t think much of Music Land when it first appeared. Today it is ranked among the great cartoon shorts, a brilliant version of that staple of 1930s drama: the battle between classical and popular music. Here, the forces are separated into two hostile islands, the Land of Symphony and the Isle of Jazz, ruled by a feuding King and Queen. On the sly, the Jazz King’s son (a little saxophone) has fallen in love with the Princess of Symphony (a young violin). To see his sweetheart, the Prince steals across to the land of Symphony (paddling the wooden keyboard of a xylophone with a half note as an oar). But he is captured by guards armed with violin bows and imprisoned inside a giant metronome. This occasions a musical war between the two kingdoms—a bombardment of Wagnerian notes shot from a royal organ countered with artillery fire from jazz brass. When the two monarchs see that their children are in danger, they call off the hostilities and agree to a double marriage. Both children and parents marry on the musical bridge of harmony.

Leigh Harline’s musical training comes into full play. Beethoven, Wagner, and an 18th century gavotte jostle with bugle calls, snippets from musical shows, and two original jazz compositions: “The Saxes Have It” and “Jazz Fireworks.” Harline even works in a musical joke—having the jailed prince write out his message to his father with the musical notes for “The Prisoner’s Song”—one of the rare instances of a current hit tune being used in a Symphony. In a film lacking spoken dialogue, the ultimate tour de force comes in the wedding scene. Vows are squeaked out on violin and viola strings.

The charm and ingenuity of the film’s design was acknowledged almost immediately. In 1937 the film won the first animation prize offered by the Venice International Film Festival. More recently, the Simpsons paid tribute to the film in a Couch Gag episode called “Music Ville.”

COCK O’ THE WALK

COCK O’ THE WALK

The Cock o’ the Walk, a famous prizefighting rooster, pays a public-relations visit to a country barnyard and is soon surrounded by adoring hens. One of them is a young pullet who has been carrying on a romance with a local bumpkin rooster, but instantly abandons him at first sight of the champ. The hick, publicly humiliated at the loss of his girl, challenges the champ to a fight and is further humiliated when the champ easily defeats him. But the tables are turned when the pullet discovers that the champ has a wife and a large brood of youngsters at home. Returning her attentions to the hick, she gives him a kiss that inspires him to return to the ring and pummel the scoundrel. The Disney story department had started with a very different story outline, but it was this revised plot that found its way to the screen late in 1935.

One of the most striking features of Cock o’ the Walk is its music. A majority of the cartoon’s score—more than half its running time—is given over to a contemporary hit song, Vincent Youmans’s “The Carioca.” This song had been introduced in the movie Flying Down to Rio, released just two years earlier, and now it became the dominant musical theme of Cock o’ the Walk. This was an extremely unusual occurrence. To be sure, the use of music from outside sources was a basic part of the Silly Symphony aesthetic; we’ve heard ample evidence in earlier recordings in this set. But most of these “borrowed” tunes were classical or traditional themes, and most of them were quick snippets, juxtaposed with each other for contrast and variety. Here, instead, “The Carioca” stands alone as the musical foundation of the entire score. What makes this especially interesting is that Flying Down to Rio had been produced in 1933 by RKO Radio Pictures—and now in 1935, coincidentally or not, RKO was mounting a concerted campaign to take over the Disney distribution contract from United Artists. In the end their efforts were successful, and they did win the Disney contract. We’ll hear music from the RKO Symphonies later in this collection.

On screen, the “Carioca” begins as a romantic dance for the champ and the pullet, but then escalates into a spectacular barnyard production number, reminiscent of the Busby Berkeley numbers in live-action musicals. The rest of the score is a patchwork. All the music preceding the “Carioca” (except the main title) was composed by Frank Churchill; all the music following that number is the work of Albert Hay Malotte—a distinguished composer in his own right and a recent addition to the Disney staff, here making his Symphony debut.

Still available!

This set is now out of print, but can still be purchased on Amazon.